Can You Tell Me the Name of My Rose?

Cassandra Bernstein, California

Reprinted without her photos, and condensed, from the autumn Journal of 2006.

Editor’s comments in square brackets.

Identifying roses

On my excursions to collect and identify roses and on the internet, I occasionally encounter gardeners who would like me to identify a rose in their garden. I can rarely offer help, since most of the “old roses” are Hybrid Teas. But occasionally, a real find is hiding in a garden, waiting to be reintroduced into commerce. With time and patience, such roses can be studied and sometimes identified by following a simple protocol.

Preserve the plant.

This sounds obvious, but like most simple truths, it’s easy to forget.

If the rose is in a garden, the gardener should not prune it harshly or otherwise change its natural shape. Roses are remarkable in their ability to respond to training. Occasionally that training can lead to an atypical shape for the variety. In general, however, a rose left close to its original shape will be easier to identify.

If the rose has no obvious keeper, consider every abandoned rose as an endangered rose. Remodelling, new construction and ignorant gardeners are great threats. Therefore, the first step is to collect cuttings for propagation. Take a variety of sizes of wood, from softwood to hardwood. If possible, dig up a sucker. Do everything you can to propagate that rose. The window of opportunity to save and identify such plants can be very narrow. But do balance this against your responsibility not to endanger the mother plant by over-collection. Never remove the mother plant unless it is in imminent danger of destruction by external forces, eg. construction equipment.

Photograph the parts of the plant.

Most gardeners think the bloom is the key identifying characteristic of the rose, for the bloom is usually what attracts us in the first place. For identification, however, the bloom is notoriously fickle. Both shape and colour vary with climate, soil and season. Subtle colour variations with fine, cupped shape in one climate can translate to a bloom with half as many petals revealing the stamens in another. By all means, try to photograph a typical bloom. That means a fresh, fully open flower, not a bud, but don’t stop there.

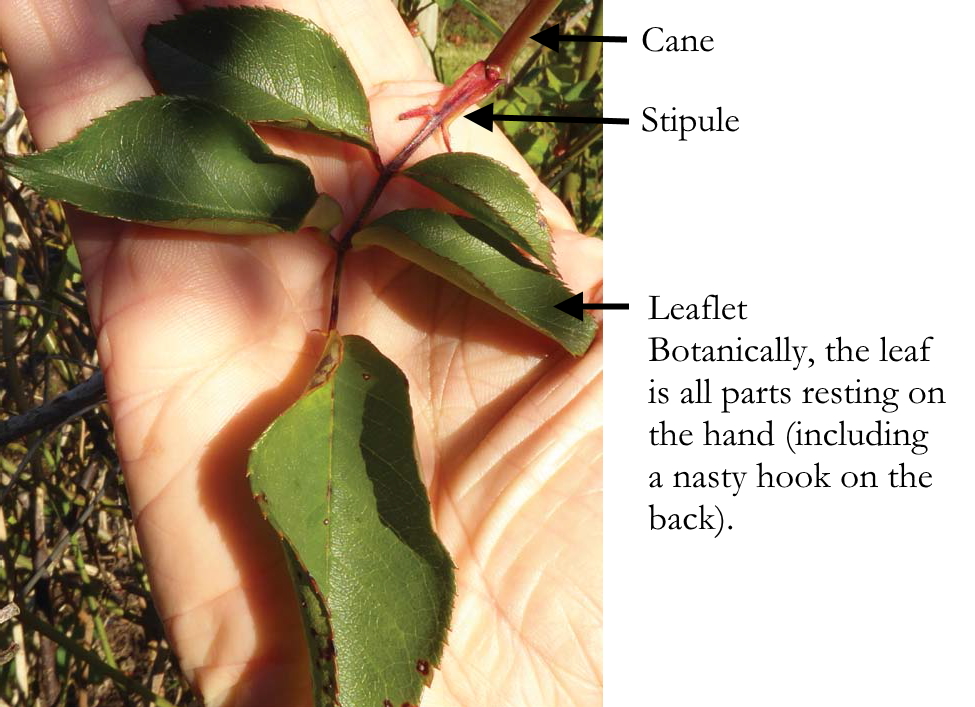

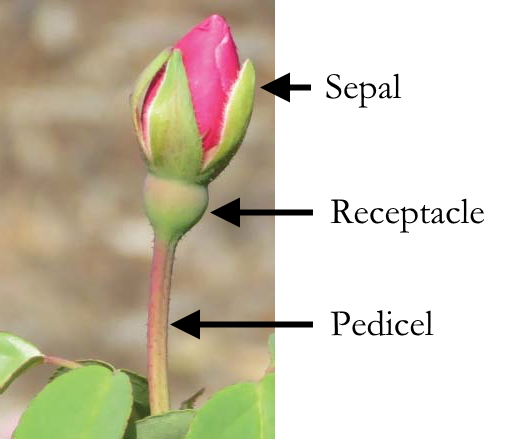

Key identifying characteristics include foliage, stipules (the small, wider appendage where the leaf attaches to the cane), armature (the prickles), sepals (the usually-five green, star-like growths that hold the bud closed and cradle the open bloom), receptacle (the small green goblet-shaped structure containing the rose’s reproductive organs at the base of each bloom), pedicel (the tiny stem that supports the individual bloom), scent, bloom and growth habit, the latter two being the most variable. I subscribe to the view that each rose has a “look”, an overall quality like that of a super-model, that can sometimes be captured with words, sometimes with the camera. Occasionally that look will, with your other information, instantly distinguish that rose from others. Whole-plant shots are essential for conveying a sense of the entire rose.

For botanical nomenclature, see the excellent Field Report of Rose Characteristics, by Judy Dean, Lynne Storm and Bev Vierra.

Photograph the foliage, stipule and armature.

Old growth and new growth can vary in colour and quality. For example, new foliage may emerge russet and then turn medium green, or new prickles may emerge burgundy and age to tan. Try to photograph both. I use my palm, an unprofessional but handy tool, as a common referent in my pictures. It provides a check for scale and colour. By all means, include the stipules, where the leaf attaches to the cane [branch], in close-up, as the stipule can provide clues as to breeding.

Photograph a well-developed bud about to open, for the sepals, pedicel and receptacle. Small details, often invisible to the mature gardener without the aid of a hand lens, can be instructive for identification purposes. Each of the structures supporting the bloom can be smooth or hairy, and, if hairy, glandular as well. If handling the buds leaves a resinous scent on your hand, make a note of it.

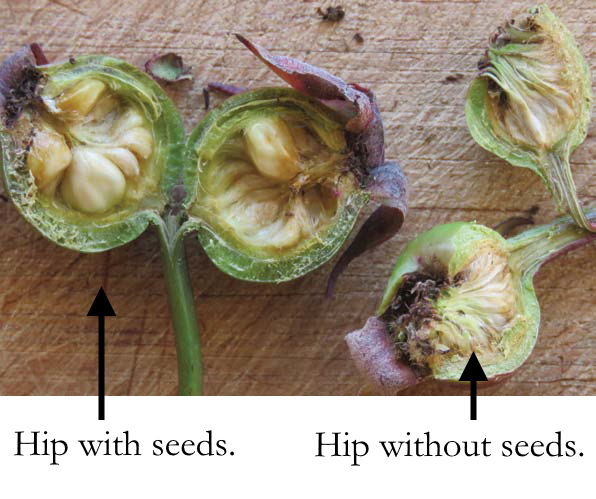

Photograph the hips / heps.

Roses bear fruit, and the colour, shape and quantity of hips can be distinct. This may require a separate photograph late in the season, after the fruit has ripened. Even the absence of hips can be instructive. [Check whether the hip contains seeds. Some roses, eg the rose sold as Mme Berkeley, produce the occasional hip but no seeds.]

Photograph the bloom.

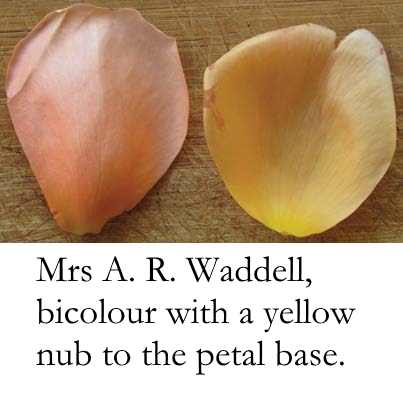

Try to capture the colour; this is no easy task. Colour reproduction is affected by monitor settings. Ideal conditions for shooting roses are slightly overcast days. If the rose blooms in multiples, be sure to capture a shot of the entire spray. [Photograph front and back of petals side by side, if they are different colours.]

Photograph the whole plant.

In many ways, this is the most challenging task. Surrounding plants, weeds and structures often interfere visually, just as it can be difficult to capture a certain expression on the face of a child. Try different angles and lighting. Remember you are trying to capture the rose’s unique “look” rather than a fashion shot showing it at its best.

Name your rose.

If no-one immediately recognises your rose, give it a study name, and use it consistently. This is a simple essential task. Tie the name to the geographical location where you found it. If you have an idea of the classification of your rose, include it as a component of the name, eg “Arcadia Louisiana Tea”. Study names are shown in double quotation marks. [With cemetery roses, the name on the nearest grave should be included. But remember that the name should be manageable on labels.]

Often, an unidentified rose will be found in different locations. Even that bit of information is useful, for it indicates that the rose was once in commerce and not simply a chance seedling.

Preliminary Research.

Try to track down the owner of the rose. Determine the age of the garden. Note whether the bloom repeats. [Scent? Does it climb? Does it sucker on its own roots?] Try to arrive at a likely class. Most species look like nothing else you’re familar with. It is very helpful to identify the colour relative to a well-known rose.

A frustrating fact of collecting roses is that the overwhelming majority are common cultivars or rootstocks. A passing familiarity with local rootstocks will make the job easier.

Disseminate the photographic details.

Documenting your findings on www.helpmefind.com gives wide access to them [but rarely produces an answer]. One small but useful tool is to include keywords such as “found roses, rose rustling, unidentified roses, old roses, heritage roses” in your HTML code, so that internet search engines will reference your page.

Present Your Rose to a Rosarian.

Take good quality blooms with leaves or a small healthy plant in bloom to a large collection or a rosarian. Rose lovers vary enormously in their ability to know one when they see one, and the impressions of some may be less helpful because their climates are so different. There is a handful of rosarians who have seen thousands of roses and have the kind of memory to recall their similarities and differences on sight.

If it is a good rose, spread it around. Make it available to Heritage Roses Groups and nurseries that specialise in older roses. Remember, there are thousands of varieties, cultivars and species. Don’t despair: if enough rosarians see your rose, sooner or later, one may recognise it, if only by happenstance.

🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹🌹

The WFRS Heritage and Conservation committee are going to try out a rose ID service: email info@worldrose.org headed ‘Rose ID panel’. We will observe.